Vortex (Gaspar Noé, 2021) Review

Fragments of a forgotten love in the silence of senescence.

In early 2020, Gaspar Noé suffered a brain hemorrhage that nearly cost him his life. To make matters worse, his mother died of Alzheimer’s disease in his arms1. Having experienced both forgetfulness and death firsthand, it’s only natural that Vortex reveals one of Noé’s most human sides.

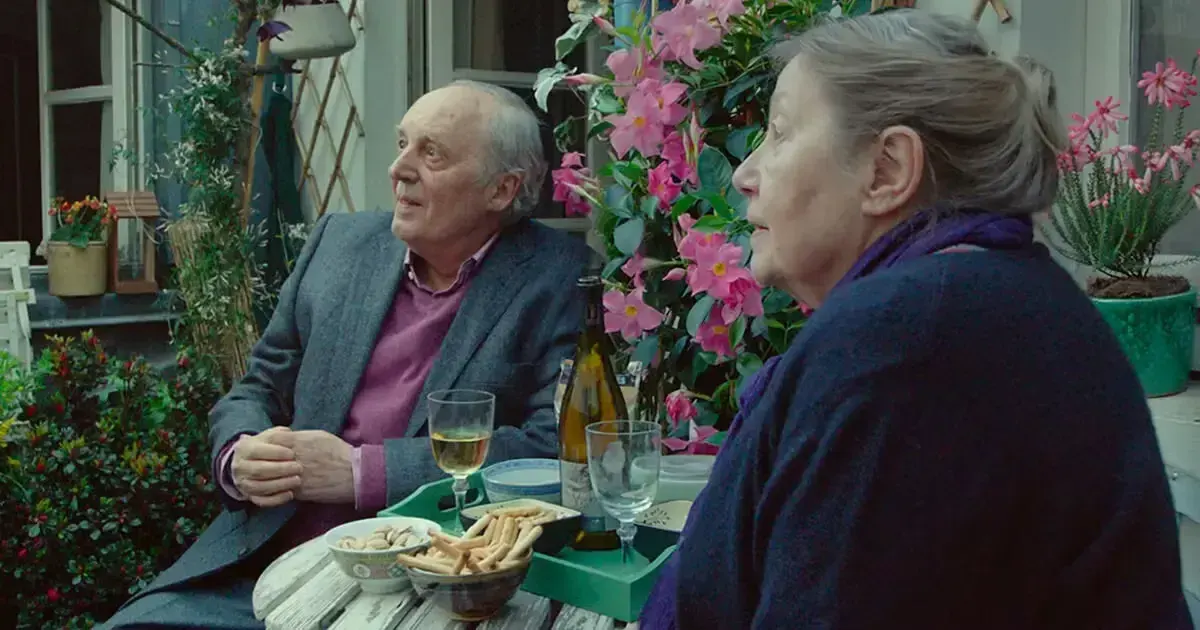

Unlike the psychedelic journey of Enter the Void (2009) or the Dionysian whirlwind of bodies and violence in Climax (2019), Vortex—a title that aims higher than it reaches—offers a more introspective and measured look at life through an octogenarian couple played by Dario Argento and Françoise Lebrun. The Italian director returns to his roots as a film critic, while the French actress, famous for her role in the Nouvelle Vague cult classic The Mother and the Whore (Jean Eustache, 1973), returns to the big screen, much as Emmanuelle Riva was resurrected from her illustrious past with Resnais by Haneke in Amour (2012).

In fact, there are striking similarities between Noé’s work and Haneke’s: both plots revolve around a husband coping with his wife’s Alzheimer’s. However, each filmmaker approaches the theme from a different prism. Vortex unfolds at a deliberately slow pace from the very beginning, opening with a credits sequence that would conventionally appear at the end of a film. Then, as the protagonists are introduced, their names appear alongside the director’s, each accompanied by the birth year. This is not a mere informational detail, but rather a device that immediately and powerfully articulates Vortex’s axes: the passage of time, the finiteness of life, and how memory—and cinematic art—preserves what would otherwise fade away.

From that point on, the film takes on a lethargic rhythm—as if dying—orchestrated through a split-screen format that shows both characters simultaneously. This visually compelling artistic choice represents the fragmentation of their relationship: two wills split by age and memory that move in unison yet at different tempos. Though the division suggests separation, framing them together signifies solitude within companionship. The pendulum swing between separation and proximity is reflected throughout, as seen in the long takes of them wandering the house without crossing paths.

In their relationship, we see how ego can interfere when grace and patience are required. Yet, we can somehow sympathize with Dario, who seems overwhelmed and reluctant to enter a care home, afraid of leaving his past behind, manifested as books. This predicament prompts his son’s (Alex Lutz) intervention, who also wrestles with his own problems and fails to ease the family tension—his drug addiction erects a huge barrier between him and his relatives.

Most of the (scant) script revolves around vague despair and complaint. The rest consists of Argento’s clichéd, shallow musings on life’s dreamlike nature, which feels more like a failed attempt to give the film a more Bergmanian air. Additionally, there are squandered narrative arcs, like the book he’s writing, which comes off as a vehicle for Lebrun to emphasize her mental decline. Similarly, Argento’s subplot with his lover is utterly irrelevant. It was a demand that the Italian filmmaker made to Noé in order for him to act in the film, so no wonder it feels so forced.

These examples demonstrate that almost everything in Vortex is half‑finished and never manages to convey a clear message beyond the inherent topics of Alzheimer’s, such as life’s fragility and the ephemerality of things. As in Irreversible (2002), “Le temps détruit tout” would have been an appropriate final message for the film, albeit with far less impact than the filmmaker’s most controversial work.

Vortex achieves poignant moments in its final act, but they lack the emotional power that Noé intended due to the the couple’s lack of chemistry in the first half. The project’s “arthouse” nature, which focuses on style rather than developing the couple’s relationship, prevents a genuine connection with the characters—quite the opposite of Amour. Trapped in the vanities of its own artifice, the film spins in a whirlwind. The split-screen format, meant to recreate mental separation, ends up as a morbid exercise in confinement. Overall, the film fails to express anything that couldn’t have been conveyed more powerfully in a shorter amount of time.

Noé aims to make this topic banal without embellishment, to instill in us the frightening thought that the protagonists could be any of us. However, Vortex ultimately falls short of delivering the profound meditation it aspires to by neglecting the essential idea of a work about worldly decay: life must be shown for death to have meaning.

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

Buchanan, K. (July 16, 2021). “Cannes: This Is the Only Thing Gaspar Noé Fears About Death”. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/16/movies/gaspar-noe-brain-hemorrhage-vortex.html ↩