Pathologic 2 (Ice-Pick Lodge, 2019) Review

A Camus-esque interactive story that manages to be more engaging than I ever expected.

It’s definitely not an easy task to put my thoughts about Pathologic 2 into words, mainly because I’ve never played anything like it before. In fact, I’ve spent far more time writing this review than playing the game itself. It’s definitely one of the most ambitious projects I’ve ever seen in a video game in terms of story and one of the few pieces of media that has captivated me the way it did.

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Before you start

Where once a person was, now but a gap remains. This rupture will not mend.

Although this review of Pathologic 2 (no comparisons or details of Pathologic Classic will be discussed) is spoiler-free except where explicitly noted, I strongly encourage you to play it knowing as little as possible, so stop reading this post if you haven’t played it yet and intend to do so.

In order not to ruin the intended Pathologic 2 experience, do not use a guide before or during the game, as difficult as it may seem at first. Also, do not use previous save files if you screw it up at some point. Face the consequences of your actions and ultimately do not gamify it. You’ll never play anything like this again, except for Pathologic Classic, and you only have one chance to play this virgin, so don’t waste it.

A cryptic yet riveting story

Since I started watching Russian and Soviet cinema, I developed a deep interest in their culture because of their poetic approach to life, which eventually led me to read Slavic literature. Most of my favorite books belong to this stream, where we can find writers like Dostoyevsky, whose bibliography made an important impression on me because of the way he portrayed the characters in his works. They feel alive, real, and complex enough to sympathize with them and to make the reader ponder about the human condition and all the psychological traits that make us a complex species.

It wasn’t until now that I finally had an experience similar to what I described above in a video game. It’s no coincidence that the Russian studio Ice-Pick Lodge is responsible for such a feat. They were also the developers of the first Pathologic game, released in 2005, and The Void.

In this second installment of the Pathologic franchise, we play as the Haruspex, also known as Artemy Burak. He’s one of the three main playable characters in Pathologic Classic and the only one available in Pathologic 2, as the other two routes are still in development.

I won’t go into too much detail about the plot in this section, because the less you know about it, the better. Suffice it to say that he receives a letter from his father asking him to return to his hometown, the Town, and accept his father’s succession, as Artemy has been away for several years to study medicine. He and we, the players, will have 12 in-game days to fulfill (or not) his father’s dying wish.

The story is dense. Very dense. It’s told through a theatrical narrative where every character is connected to some aspect of the Town that may not be obvious at first. Some of them we won’t interact with as much because the title relies on the emergent narrative, without forcing the player to complete any quests. This means that we may miss the chance to meet some characters or some aspects of the story, as time doesn’t wait for us, and neither does the Town and its people.

Even though I can see why some characters might be more substantial to the other two routes, some feel irrelevant and unnecessary. They could have been fleshed out more during Artemy’s story arc, or at least given more context as to why they’re not as important to him, so that we don’t feel like we’re missing out on aspects of the plot that aren’t really explained in the Haruspex route. This feeling gets stronger as the days go by, as there are more characters in the story and less time to interact with them.

The script itself has an abstract and tetric feel to it, just like the whole game. It’s hard to figure out what some people want from us, especially the Kin, because everyone has their own goals. They see Artemy as a means to their end. It’s only towards the very end that some things finally make sense, as important aspects of the story are explained through metaphors and steppe language influenced by the steppe folklore. However, there will still be unanswered questions, as the Haruspex route only covers a third of the whole picture (who the hell are The Powers That Be?).

We can respond to something a character tells us by choosing one of the answers Artemy would say. Since he was born and raised in the Town, it makes sense that he already knows details about it that we as the players don’t. This mechanic reveals details of the story in a subtle and clever way, which is a fantastic approach because it doesn’t feel like the game is treating us like toddlers (something that some video games unfortunately do these days).

Even though the world is dark and gloomy, the Haruspex’s sense of humor will make us laugh and relieve some tension due to his sassy1 nature. There are also funny little details like the description of the Cemetery (“You will always be welcome here”), and references to pop culture, like the Pink Floyd reference in the description of the Factory (“Welcome to the Machine”), and three structures named Stairway to Heaven, as a nod to the Led Zeppelin song.

Pathologic 2 forces the player to make difficult choices throughout the story, which I’ll discuss in more detail in the Why this game is a good liar section. Beyond what the title suggests, the choices will prove the point that there is no winning in this game, and that every action has side effects that we’ll have to bear. There’s no point in loading the previous save file, because making what appears to be the “right” decision may have a negative consequence in the future that we are unlikely to foresee.

A brilliant combination of mechanics

For the first few days, it feels like the title doesn’t want you to play it, but if you stay interested in learning its mechanics, its story, and its world, it will eventually reward you. It’s like a wild horse that needs to be tamed to be ridden comfortably.

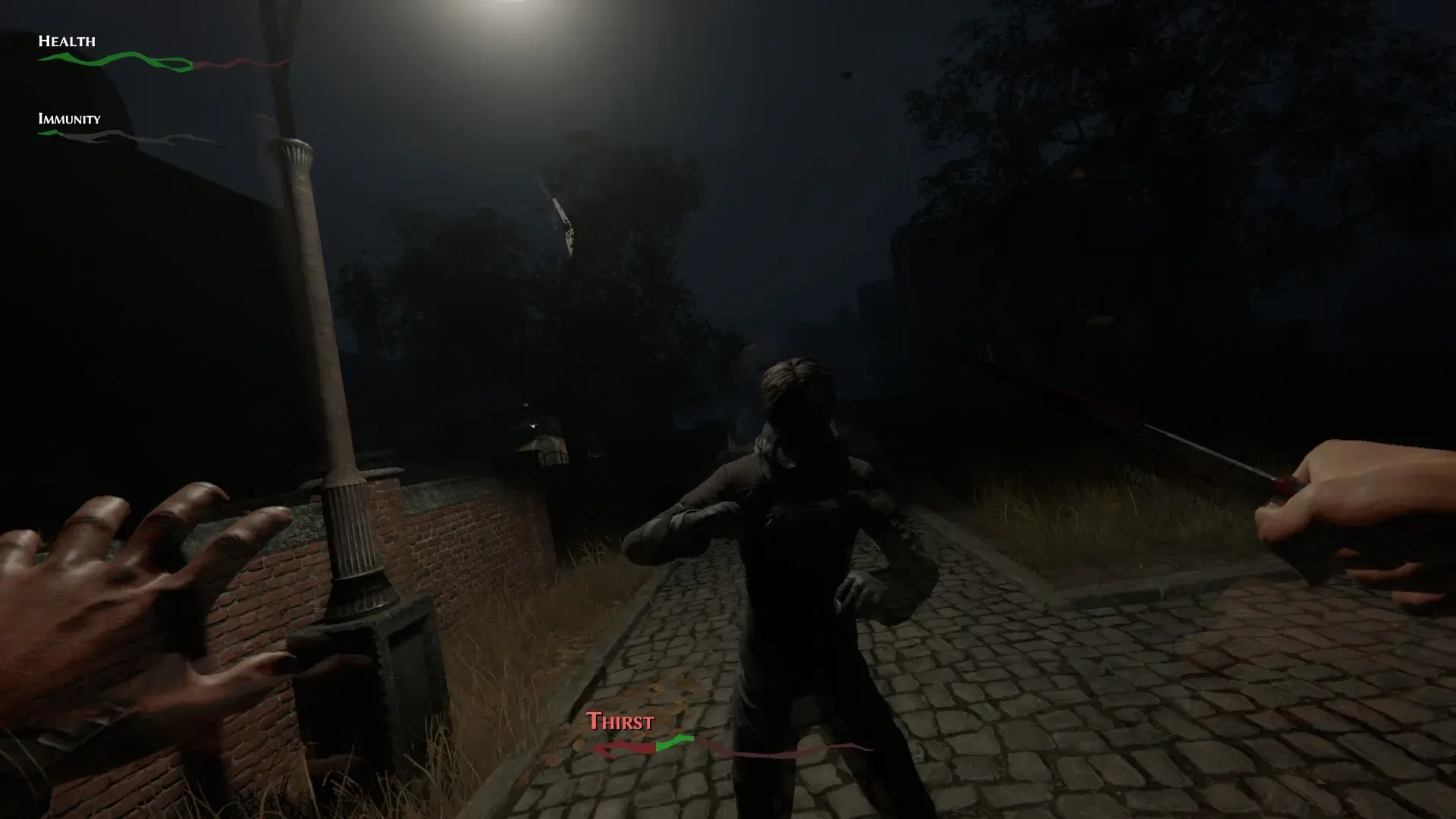

The way the title blends ideas from a variety of genres is interesting, even if it doesn’t really reinvent the mechanics it implements. It’s hard to pin it down to a specific genre, as it’s a first-person shooter that mixes traits of an open-world survival craft system with some features of Western RPGs. The closest comparison that comes to mind in this regard is the Fallout franchise (the 3D games).

A large part of the gameplay involves figuring out the most efficient way to do the day’s quests, the order in which to do them, gathering resources since the game rarely lets you stockpile enough to feel safe, trading with NPCs, and trying to keep hunger, immunity, and exhaustion levels away from killing you. That last part will probably be the one that makes you think the game is too hard. With each passing day, resources become scarcer, making survival an even greater challenge for both the player and the Town’s inhabitants.

Time is always running, except when you are in the menu. There’s too much to do in 24 hours, so we have to prioritize our goals for the day. Sometimes we have to spend time taking care of ourselves instead of helping others or doing quests, which can result in not being able to complete a quest or some characters dying.

People aren’t exaggerating when they complain about the difficulty, because according to the Steam achievements stats, only about 9% of players have reached the most common ending. Despite how hard the game may seem, I encourage you to play it at the intended difficulty. Otherwise, the game’s ludonarrative won’t feel as balanced as it actually is, because if the game keeps telling you how hard the situation in the Town is and you manage to survive with ease, it would lead to blatant ludonarrative dissonance and potentially ruin the Pathologic experience.

Given how hardcore Pathologic 2 is, I’m even surprised that it gives the player map markers and a conceptual map of Haruspex’s thoughts, which I appreciated considering how uncondescending it is.

If you’re struggling so much with the game that the Fellow Traveler offers you a deal, do not fall for it. The game wants the player to feel the consequences of the their failures and overcome them, because that’s a crucial point of Mark Immortell’s play: to struggle and not take the easy way out. No pain, no gain.

As for the survival aspect, there are items that make our lives easier, whose use is not fully revealed at the beginning. It’s important to read their descriptions in depth, as they will also give us insight into details of the story. Keep in mind that some of these descriptions will change as more story details are revealed, so be sure to check them from time to time.

As if all the survival mechanics weren’t enough, we also have to deal with hostile bandits who will attack us as soon as they see us. I only used a knife in the few fights I had during my first playthrough, preferring to avoid any unnecessary hassle. The control of the melee weapons is simple but effective. For the sake of completeness of this review, I used the rifle to form an opinion on the shooting aspect, which felt the same way as the melee mechanic: simple but getting the job done. The fistfight gameplay, on the other hand, is quirky and uninviting. This might be intentional, though, since Artemy is a doctor and the game doesn’t explicitly tell us that he’s a particularly good fighter.

The ludonarrative of Pathologic 2 is beautifully implemented, as the survival mechanic fits the sense of desperation that the Haruspex and the Town are going through. The exceptional balance of combat, economy, hunger, thirst, exhaustion, and infection accurately reflects the core message of the game: sacrifices must be made in pursuit of a greater purpose.

Another interesting mechanic that might be worth figuring out for yourself.

Even though this may seem like an unnecessary punishment at first due to the already high difficulty of the game, I liked the concept of applying a penalty to all of the player’s saves every time we die. What’s even better is that you have to start a new game to undo all of these penalties, so we have to think carefully about the potential rewards and losses of an action that could mean our death. There may be a point of no return, where we enter a death spiral and starting over is the only way out.

The Town as a living entity

The game’s subtle details are tasteful. What surprised me the most in this regard was the effect of the escalation of the crisis on the Town and its inhabitants. The worse the situation gets, the more chaotic and dangerous the streets become. It gets to the point where even neutral NPCs are running around the streets, trying to get home as fast as possible or running away from some bandits.

The interaction between the NPCs is fantastic. We can witness a fight between the Town authorities and some bandits and accidentally get shot if we get caught in the middle of the conflict. The Town’s authorities will loot what they can from the dead bodies, while some others won’t bother to loot what some miserable outlaws are carrying.

Speaking of NPCs, the lack of common Townsfolk models is kind of a feature, because it makes it easier for us to identify what they’re trading and what value an NPC model gives to certain items.

The sound design is also an essential part of creating the gloomy environment of the Town. As random as some of the sounds may seem at first, you start to realize that they’re not there by accident, because they’re actually conveying information that will probably fly over our heads during the first few hours. They help us to get more insight into the lore and obtain side quests.

The fires in the streets, which become more and more latent as the days go by, also add to the sense of helplessness and chaos that the Town and its people are experiencing.

Technical and artistic aspects

The performance of Pathologic 2 is terrible. I have a RTX 3070 Ti and an i5-12600k and the loading time that it takes to enter a building is ridiculous. It’s not enough to ruin the experience, but it’s definitely a hindrance at times. Maybe you’ll find this Steam guide helpful to improve the performance a bit.

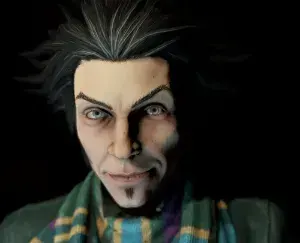

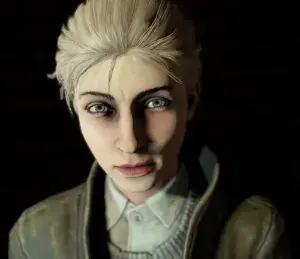

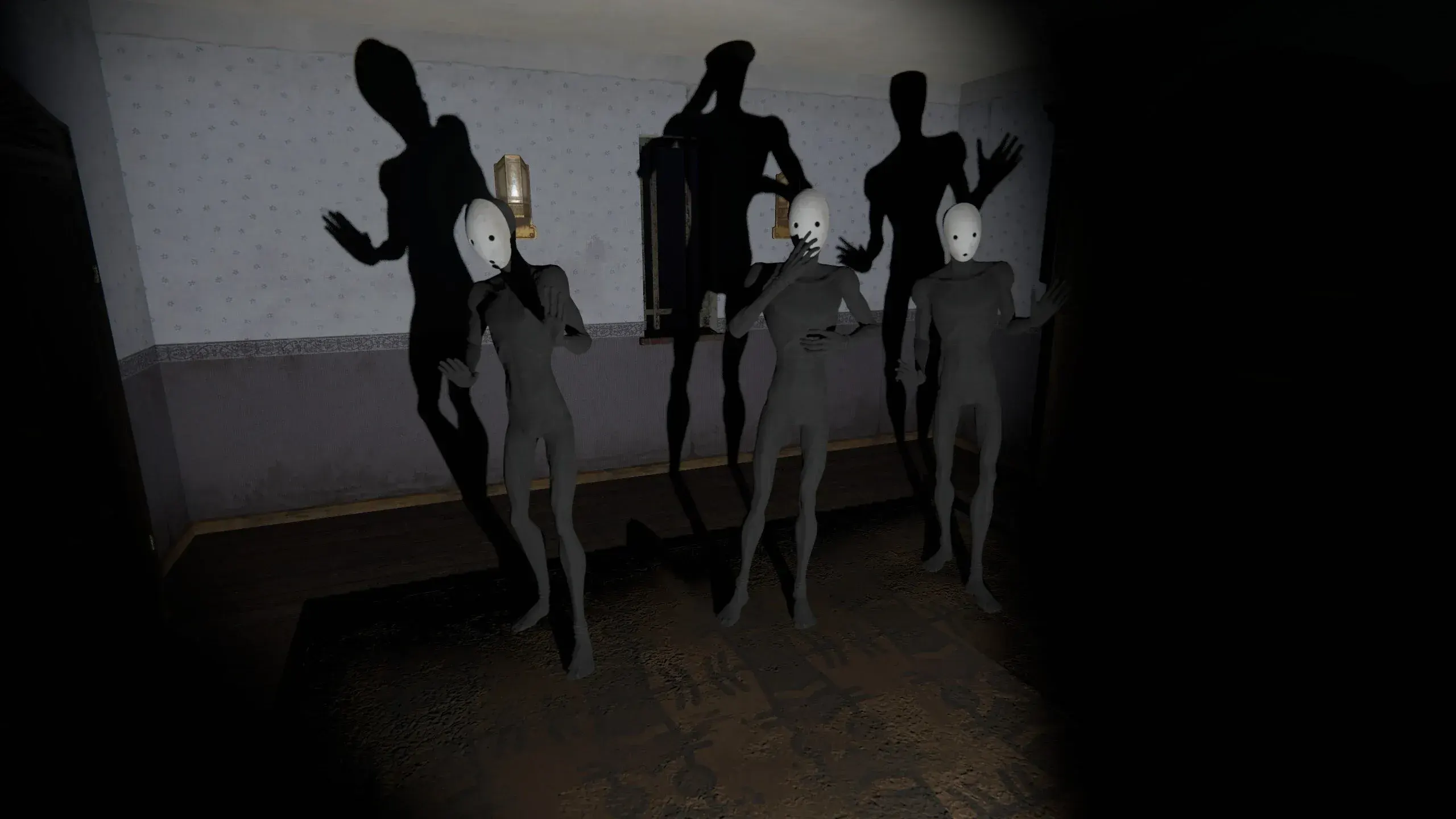

As for the graphics, even if they aren’t outstanding, they fit the artistic style of the game. What stands out, however, is the character design. A good portion of the cast is really good-looking. This is the first time this thought has crossed my mind while playing a video game.

Here are a few that reflect what I mean:

The architecture of some of the buildings is astonishing, especially the Cathedral and the Polyhedron, which stood out out to me. It makes sense that they are such impressive buildings, given their importance in the game. The rest of the Town is uniform and consistent, appropriately representing the architectural style of the time period in which the game is set, the 20th century.

Unfortunately, I don’t speak Russian, so I played the English version, which reads superbly. The vocabulary is rich and the script is well written, on a literary level. However, Pathologic 2 is one of those Russian works that makes me wish I knew Russian, because it seems to be a difficult language to translate without losing some of the full meaning of the descriptions, puns, double entendres, and subtle nuances that enrich the script.

Along with the aforementioned somber sound design, the dark soundtrack also adds a haunting tone and a disturbing sense of hopelessness. This track can convey what I mean better than a thousand words.

It’s also worth mentioning that the soundtrack has a piano track composed by Erik Satie, which is Gnossienne No. 3. It gave me goosebumps the first time I heard it in the game, and made me laugh when the Haruspex confidently said that it was a Liszt composition.

Why this game is a good liar

There will be spoilers in the following section.

It doesn’t matter if you don’t do any missions, whether they’re main or side quests. On day 10, Aglaya will always realize the connection between the Sand Plague and the Polyhedron. The missions are only useful for gaining insight into the story, “nothing” else. The only one that has a direct impact on the plot is the one where we have to find the courier before 22:00 on day 11. If we fail, we get the Late ending.

This completely shocked me because the game really made me feel like the decisions had an impact on the story. It will play out virtually the same regardless of which people are left alive, as there are the same 4 possible endings no matter what you do during the course of the story (except for the deal with the Fellow Traveler). While a part of me wishes the game was more plastic in this aspect, we have to keep in mind that there are two more playable routes whose stories are connected, so I can somewhat understand why the plot is as rigid as it is. All in all, it’s really good at tricking us because the story unfolds consistently according to our choices.

However, as deceptive as Pathologic 2 may seem, our reading of the endings can vary subtly (or widely) depending on who’s left alive. For example, in the Diurnal ending, the engagement between Khan and Capella could be interpreted differently depending on which of the Kains or Olgimskys is/are dead. In fact, the meaning would be completely different if they were all dead. The same goes for the Nocturnal ending if Taya, Aspity, and Oyun die. What would happen to the Kin in the future without them? It’s up to us to draw conclusions from these outcomes.

Aside from these story aspects, the mechanic of the descriptions changing depending on what point in the story we are at is a good idea, but I don’t think it’s implemented well enough. I remember I was about to restart my first run on day 4 because I got infected and didn’t know how to cure the infection. Out of desperation, I checked the items I had stored in the Haruspex’s Lair and found out that the description of a shmowder that I randomly got on day 2 had been changed its description to explicitly state that it cured the infection. I may have skipped some dialog where we learn the true use of shmowders on day 4, but I’m pretty sure the game didn’t explicitly tell me their use enough to change the description.

Digging deeper into the story

There will be spoilers in the following section.

In addition to the influence of Slavic literature, I believe that Nikolay Dybowski, the founder of Ice-Pick Lodge and the mastermind behind the Pathologic universe, was heavily inspired by Albert Camus’ book The Plague and Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal. Without spoiling anything related to them, I’ll just say that I felt a similar way when I first played The Last of Us and then watched the film Children of Men.

Prologue

Pathologic 2 uses the in media res technique, which places the player on day 12, the final day. The first person we talk to is Mark Immortell, who blames us for Burakh’s seemingly atrocious performance. The game guilt-trips us right off the bat for the chaotic situation presented during the prologue. It’s a fitting premise for the title, as we’ll be held accountable for the consequences of the Sisyphean task that we’ll be entrusted with.

Nevertheless, Mark gives us another chance to reconstruct the situation. This is when we are transported to the train where we meet the Fellow Traveler, and through what it feels like a fever dream, some tutorials of the game mechanics take place, such as fighting, trading, and getting water.

The most important aspect of the prologue is how accurately it introduces Pathologic 2 as a chaotic and confusing world where nothing makes sense at first. What kind of train stops right in the front yard of a house? Why does the Fellow Traveler turn into an Executor just before getting off the train? Why is there a laughter in the background as we are about to leave the house? Is this a dream? Why are we looting the items in the furniture when we don’t even know what’s worth taking? Are the laughs directed at us for wasting our time taking useless items? What if they’re a reflection of the developers, making fun of us for not knowing what kind of adventure we’re about to enter once we walk through the last door?

As soon as we enter that door, the game starts, as if it were a portal to an alternate universe. Have we been Artemy all this time, or just another aspiring actor to play the role of Artemy? What’s this game all about?

Act I

The beginning of the game shows us the roughness of the Town and the dire situation that it is going through at the time of our arrival, as supplies are scarce due to trains not arriving. It covers only the first day and serves as an introduction to the Town and its people, including the Kin, and the three ruling families that represent the political division of the Town. In addition, the Town blames Artemy for the murders of Isidor Burakh (Artemy’s father) and Simon Kain, which took place the night before he arrived, for no other reason than he was the last person to arrive in Town.

From the very beginning, the game puts a strong focus on the children, who end up being an essential part of the plot and the ones who make our survival easier thanks to the bartering, which is a fundamental mechanic to get down as fast as possible if we want to survive. They don’t judge Artemy as harshly as the adults, so they’ll interact with him from the very beginning, regardless of his reputation. They’re charismatic and charming, but due to Burakh’s cheeky nature, he tends to be less than friendly with them. However, as the story unfolds, he gradually develops a genuine affection and respect for them.

One of the things that Bad Grief says when we first meet him is a good introduction to the morality of the Town:

Such is our town. You know it yourself: It’s a very good village. Beautiful people live here, infusing it with a very spiritual dream. There is no real, villainous crime here. Even the rats and the thieves are softer.

No weapons or sharp objects are allowed here, as murder is strictly forbidden. Only menkhus are allowed to cut people, as it’s considered a crime against nature if done by people who don’t know the Lines. In fact, nature is so sacred in the game that you can’t even dig a hole because it’s Mother Boddho’s skin.

Artemy is presented as almost an outsider because of his time away studying in the Capital. He’s split between the modern Town and the ancient Kin from day one, but he’s not really considered as part of either. The Kinfolk tell him that he must prove to them that he knows the Lines to be a part of them, while the Townspeople see him as part of the Kin, and even treat him with contempt. This division is still prevalent in the final choice, which is merely an extension of this dichotomy.

Act II

It starts on day 2 and ends on day 3. The situation in the Town is grim, as the trains are still not arriving and the lack of supplies is causing the prices of goods in the shops to rise. There is also a riot going on in the Termitary, which leads to a defragmentation of the Kin because those inside don’t know what’s going on outside.

Isidor’s legacy, delivered by Aspity on day 2, will make us learn the concept of how a body is divided into three layers (Blood, Bones and Nerves). This division also applies to the relationship between Artemy Burakh and the relevant characters of the Town, which is a clever way of organizing people. This distribution is not fixed, as Burakh’s relationship with them changes.

The gameplay mechanic of healing the infected is well implemented, as it feels interesting enough without becoming unnecessarily complex. Still, it can feel overwhelming at first due to the amount of information provided by our father’s reflection in Tumbler Human.

The way the plot shifts its main focus from the murders of Isidor Burakh and Simon Kain to the spread of the Sand Plague is confusing and intriguing at first, but ultimately makes sense, as both characters were the ones who made the Second Outbreak happen.

It’s interesting how the game initially presents Isidor as a some sort of semi-god to the Town, when he actually turns out to be the culprit of the whole situation. Artemy develops a more adult understanding of his father as a normal person who was capable of making mistakes. The first glimpse of this realization comes when he learns that Isidor sentenced Crude Sprawl to death during the First Outbreak by ordering the district boarded up. It occurred 5 years ago from the events of Pathologic 2, killing Murky’s parents among hundreds of people. It was a terrenal manifestation of Mother Boddho’s pain, caused by the Polyhedron.

As the justification for the burst of the Second Outbreak, Isidor tells Artemy that his goal was to fix the Town by providing it with a future. However, he didn’t know exactly what kind of future that was, so he sent the letter to Artemy to let him decide it. The moment when Isidor says this is when Artemy and we, the players, realize that he was a flawed man who failed to make the final decision.

By the way, the name of the First Outbreak and the Second Outbreak reminded me of the impacts of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Act III

This is when things start to get tough. From day 3 to day 6, we’ll focus on hospital work and learning more about the Sand Plague in order to find the Panacea. It’s not an easy task, however, because the outbreak will make our survival more difficult. At this point, the only way to cure the infection is with a shmowder, which is unlikely to get in our first run, as we won’t be aware of its effects if we haven’t played Pathologic Classic before.

The introduction of infected districts on day 4 will also make the game even harder, as the bandits roaming the streets will try to kill us as soon as they see us. Up until this point, the sense of danger is pervasive and supplies are even scarcer, so it will definitely feel like a step up in the difficulty.

Story-wise, this act is a continuous stream of information, as we find out important details about the story, such as that Young Vlad is building a well, which is taboo. We also learn that Worms can’t contract the Sand Plague, most likely because they’re chimeras and their body chemistry can’t be affected by the disease, and Aspity reveals the meaning of the udurgh. On day 6, we even visit Shekhen to gather Living Blood to make the first Panacea.

Act IV

The last and most exciting act, as the story reaches its climax. It spans from Aglaya Lilich’s arrival on day 7 to her realization that the Polyhedron is the cause of the Sand Plague on day 10. It culminates with our decision on day 11, determining whether or not to destroy the Polyhedron.

On the morning of day 9, the army arrives with commander Alexander Block. Soldiers and flame units flood the streets along with military tents and barricades. We only have a two interactions with the Commander, which don’t appear to be that relevant. However, he seems to be more relevant in the Changeling route. We don’t talk to the Inquisitor much either, but the times we do are relevant to the plot.

Each day passes more quickly than the day before, as the Inquisitor takes up residence in the Cathedral, which, according to Victor Kain. This puts more pressure on it, because time can only move on freely when there are no people around. For this reason, I can understand why the story feels rushed at this point, making the game feel chaotic and accurately reflecting the stress of the Town.

I admit that if I hadn’t already seen Twin Peaks, my reaction to seeing Mother Boddho’s heart would have been even more surprising than it already was. It’s the climax of the story and one of the biggest wtf moments that I’ve ever experienced in a video game. It’s worth noting that the spike of the Polyhedron that burrows into the heart hurts Mother Boddho, who manifests her pain via the Sand Plague. The Albinos warn us that if the Plague is removed, the living heart will be destroyed and all the wonders of the world will disappear. It’s up to us to choose the past and its wonders, or the future and the development of the Town.

On day 11, the Inquisitor sends three couriers to the Commander with orders to destroy the Polyhedron. Of all the Inquisitor’s orders, we find only one. One of the two was burned by the Bachelor, and the other was lost in the water at the Changeling’s fault. This can be seen as a dualism between fire and water, and the scientific background of the Bachelor versus the Changeling as the supernatural healer of the story. Polar opposites that both failed. It was only Artemy, the combination of the two, who was able to save the last order.

Endings

There are four endings. Two of them are relevant to the plot, while the other two are alternate endings that can be seen as a playful mockery of the player’s inability to catch the courier in time, or to fall for the Fellow Traveler’s tempting offer.

The relevant endings depend on whether or not we choose to destroy the Polyhedron. If we do, the metal spike near the heart of the Town will be ripped open, releasing enough Living Blood to make the Panacea. If we don’t, the Kin will return to the Town and most of the Townspeople will not be accepted by the Town itself. What’s interesting about this is that we are the ones who give meaning to the udurgh. Is it the Town and its people, or is it Mother Boddho upon whom the Town and all its wonders are built? Do we want to live in an age of progress and knowledge, or in an age of miracles where nothing ever evolves?

However, I still don’t quite understand why such a structure, built by visionaries, prevents children from not growing up and thus prevents the Town from having a future. It makes sense that this concept will be further explored in the Bachelor route, as he definitely knows things about the Polyhedron that the Haruspex doesn’t. He even encourages Artemy not to destroy it because he fell in love with it.

Nocturnal ending

The udurgh is the Living Earth. I choose her. Ancient aurochs return from the depths of time.

Artemy decides not to destroy the Polyhedron, and so The Town rejects the Townsfolk in exchange for the Kin finally returning to the Town. This might seem like the “bad” ending at first, since most of the Townsfolk don’t seem to recognize us because they’re in a foggy state of mind. It’s less much focused on the Townsfolk than the Diurnal ending, as only a few characters are accepted by Mother Boddho and embrace the new old ways.

Of those who are accepted, Grace, Murky, and Sticky have a special natural connection to Earth, but they’re considered as Townsfolk. The Kin never even mention them, and there’s no evidence that they are part of them. However, they are part of the world of miracles, as Grace and Murky have mistress traits, and Sticky is on his way to becoming a menkhu.

We’re often told that the earth and the Town are connected by an umbilical cord. The metaphor can lead us to think that a mother’s child can’t be permanently connected to her by the umbilical cord, because the connection will eventually have harmful consequences. Applying this metaphor to the context of the game leads us to think that the Town’s connection to Mother Boddho through the Polyhedron prevents the Town from growing and leaving the past behind. The Polyhedron, the umbilical cord, is the very same building that prevents children from growing, which they describe as a temptation too strong to resist. In the same way, it’s certainly easier for a child to be attached to its mother, because she will provide all of the child’s needs, but at the expensive cost of stunting its development. Just like what happens in this ending.

Who would have thought that the the Kin would end up appropriating the Polyhedron, a symbol of humanity’s ambition and one of the Town’s greatest achievements.

One final point that adds to my argument that this game is a liar is that if Aspity dies in our playthrough, she’ll be reborn from Mother Boddho herself, and we’ll be able to interact with her as if nothing happened. It feels like a weak attempt to cover up a plot hole, since it’s not explicitly stated that the dead can be resurrected in any way.

Diurnal ending

The udurgh is living people. I choose them. The sand pest will be eradicated forever.

Unlike the Nocturnal ending, this one feels like the “good” ending. The heart of Mother Boddho dies as a result of the destruction of the Polyhedron, which is part of Artemy Burakh’s fate, as he’s been told from the beginning to spill rivers of blood. In exchange, there will be enough Living Blood to cure the Sand Plague.

It’s a reasonable sacrifice, since the Kin, led by Taya Tycheek, will find their place in Shekhen, and the Townspeople will be able to live comfortably in the Town, which will be ruled by the children from our father’s list (at least, those who are left alive at the end). Without the umbilical cord that connects the Town to Mother Boddho, the children will no longer succumb to the desire to remain young, for progress and future are now inevitable. It’s definitely no coincidence that the embodiment of the earth has Mother in its name.

However, not everything in this ending is sweet and pink. The death of the Mother Boddho’s heart and the simultaneous destruction of the Polyhedron have a consequence that is not exactly mentioned in the game. The Polyhedron represents the concretization of the humanity’s immaterial dreams, blurring the boundaries between the material and the immaterial. It’s a place where children live out their fantasies and never grow up, connected to immortality. All of this is inextricably linked to the immaterial and the mystical embodied in Mother Boddho, in a kind of a yin-yang relationship. Her death, representing the erasure of the wonders of pre-industrial society, entails the death of the dreams of humanity. They will continue to live and progress, but the absence of miracles and innocence in its connection to Mother Boddho also robs it of its most crowning achievements, such as the Polyhedron and the existence of magical creatures like the Albinos.

This ending resonates strongly with the postmodern zeitgeist, capturing the inherent nihilism among younger generations. Despite living in the product of this progress and humanity’s mastery over nature, these children and young teens experience a sense of deprivation of basic human desires such as belonging and meaning. Our contemporary lifestyles are increasingly diverging from the tribal and wonder-filled environment in which these longings took shape and evolved over myriads of years as an integral facet of human nature.

Common aspects of the Nocturnal and Diurnal endings

Both endings share some scenes and dialog, as the game ends as it began.

The first common scenario occurs at the beginning of day 12. It’s reminiscent of the part of the prologue where we’re on a wagon train with the Fellow Traveler. Actually, we’ve never really left the train. The whole game is an ongoing conversation with the Death, our Fellow Traveler, where the train can be seen as a vehicle to meet our fate, and the train tracks as our predestined fate.

During the final conversation with Mark Immortell, he places the blame on us, the actors, for our indecision and inadequacy in adhering to the script, just as he did in our first conversation with him in the prologue. He reveals that the purpose of the play is to explore the boundaries of humanity and its struggle to conquer death. According to him, death can’t be defeated, but it can be overcome. Not by prolonging life, but by achieving something greater than the self, something that is divided into many selves. Hence, it’s logical that the role of Artemy Burakh is played by several actors throughout the play, rather than just one (unless you manage to finish the game without dying — good luck with that).

In the Nocturnal ending, we can climb the Polyhedron to talk to Townsfolk children named “Deviser”. In the Diurnal ending, they can be found on a Stairway to Heaven. They’re the representation of the Ice-Pick Lodge developers and have the same dialog in both endings.

Deal ending

It’s the consequence of making a deal with the Death itself, the Fellow Traveler, to avoid further punishment in subsequent deaths. We don’t see the consequences of that deal until day 11, when the game forces us to go to the theater.

There we are “welcomed” by Talon and Beak, who mock us for thinking that such a deal would have no negative consequences. Mark tells us that we have failed to play our part by becoming partners with Death, thus defeating the main purpose of the play. The Bachelor and the Changeling are on the stage. The former is rehearsing his part, and the latter tells Artemy this intriguing statement:

One’s as bad as the other… and the other, and the other. One thinks he’s a head above the rest, but loses heart. The other’s light on his feet, but turns a blind eye to everything that matters. And none of you can save everyone.

Play it as you like. I’ll be the one who cleans up your mess after, anyway.

Could it mean that the Changeling is the only one who can save Mother Boddho and the Town…?

After leaving the theater, we talk to the Fellow Traveler. Now that we’ve officially become his fellow traveler, we’ll travel with him on the train, where we’ve been from the very beginning. Artemy will “hold his back” and the Fellow Traveler will harvest collect his dues (take lives).

Late ending

It’s pretty much the same as the Deal ending. However, we’ll be teleported to the theater, where all the characters from the Deal ending will be waiting for us. Mark Immortell will say that we were late, that we let everyone down, and that he’s going to work with someone else who has more respect for death than we do. Very similar to the Deal ending dialog.

The conversation with the Fellow Traveler on the train is exactly the same as the one we have with him in the Deal ending.

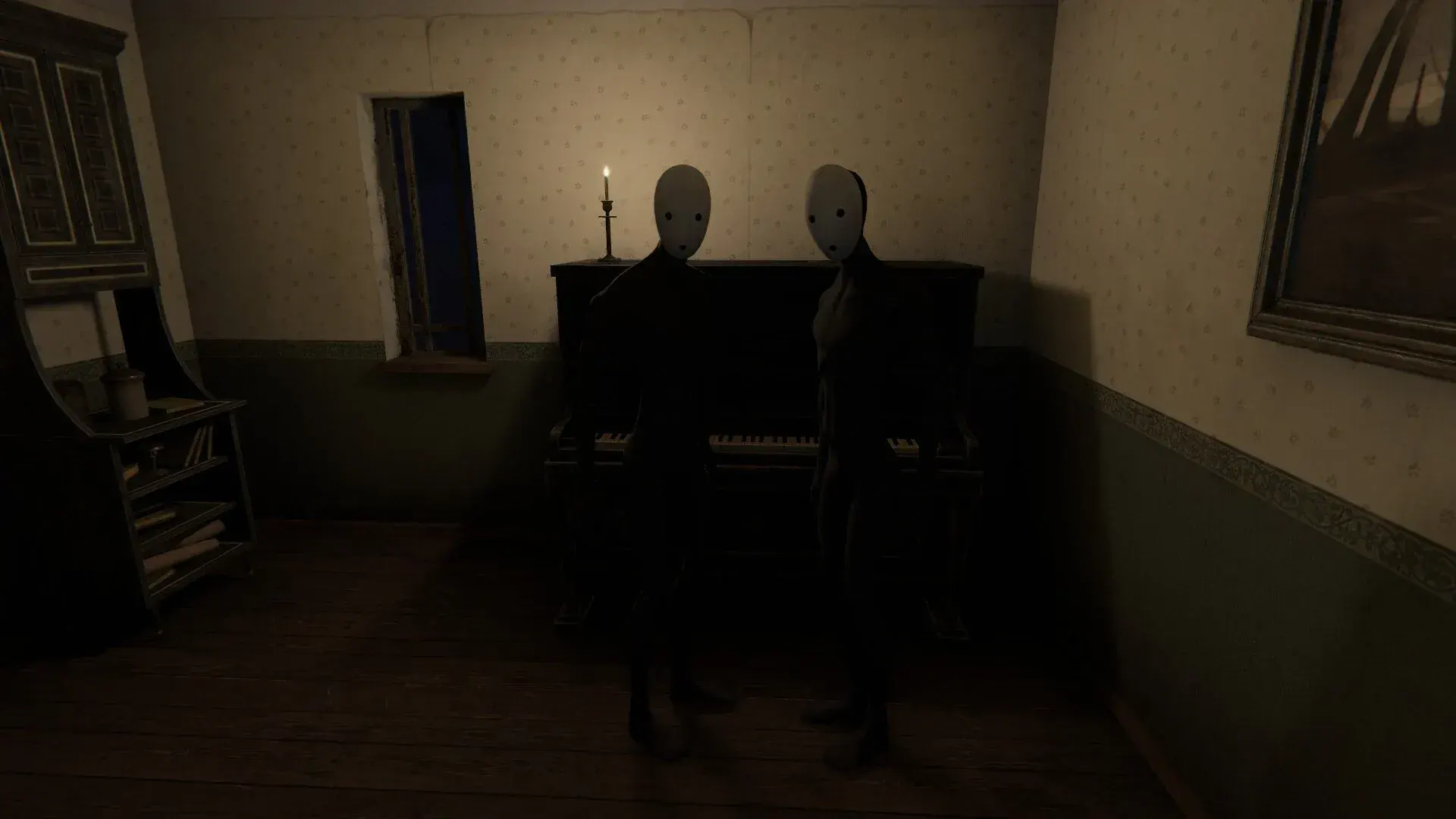

Pantomimes

They take place in the theater from day 2 to day 11, summarizing past events and also foreshadowing what’s to come. The plays are overly abstract and deal with meta-narrative aspects of the game, as does almost everything that happens in the theater (except for our doctoring duties during the Sand Plague).

Mark Immortell directs most of the pantomimes, just like the whole play. Although it’s not explicitly stated, it makes sense to think of him as the personification of Nikolay Dybowski. He always talks to the player, breaking the fourth wall to get a deeper understanding of how we deal with the death, questioning our role, our impact on the plot, and the weight of our decisions.

He is also very reminiscent of the character of The Dramatic Poet in the play Faust, because both have the idea of creating something greater than the self in order to transcend, to become many selves.

Talon and Beak are named Executors who appear frequently in the pantomimes. They have meta-knowledge of the game’s events, and will speak directly to the player throughout the game to make us question certain aspects of the story in a mocking way.

The Changeling and the Bachelor are also central to some of the plays, as is the Haruspex. All three characters interact with each other, often rehearsing their part as actors of the role that they’re supposed to play. Just like another actor like us, the player.

The first time I walked into the theater and saw Artemy was mind-blowing, because at that moment we don’t know if he’s real or not, or if we’re not real and he’s the real Artemy. Even though this aspect isn’t explicitly explained, it makes sense to think that he’s another actor with the role of the Haruspex, based on what Mark tells us throughout the game. Let’s not forget that there are several Artemy actors and that the collection of their experiences and knowledge form Artemy’s story.

While all of the pantomimes are important, I want to focus on the last one on day 11, which accurately captures the nature of the final decision. Talon and Beak have a thoughtful discussion about the future of the Town. They address the consequences of what would happen if the Polyhedron were destroyed or left as it is, and present a clash of philosophical ideas between ecocentrism, represented by Beak, and anthropocentrism, represented by Talon.

I especially like this line that Beak says during that play:

All that surrounds us is a living organism with its own blood flow and metabolism. Plague is part of this flow, frightening, but logical. It kills humans… but what is a human? Humanity itself is comparable to a microbe. Just as small, blind, and absurd.

Characters

The fact that there are NPC models that can have different names puzzled me because there were times when I didn’t know if I was talking to the same person with a different name or a different person at all. For example, some random Town NPCs have the same aspect as the Fellow Traveler.

Townsfolk

They’re a crucial part of the exploration of how power affects perception. For example, the mistresses are supposed to be loved and respected for their unique abilities, yet they all happen to come from or marry into already politically prominent and wealthy families. The early engagement between Capella and Khan is a prime example, as Capella wants to marry Khan even though she doesn’t love him, just for the sake of uniting the Kains and the Olgimskys.

However, we know that the mistress powers aren’t unique. While Maria and Capella are the daughters of mistresses and affluent patriarchs, Grace and Murky aren’t. Capella struggles with her abilities of clairvoyance and telepathy, but Grace has apparently been talking to the spirits of the graveyard for years, even though both girls are about the same age. Thus, the value of one’s abilities to society depends on more traditional means of power and inheritance, as Grace is initially overlooked as a potential peer to Capella because she is poor and has no family. The exact same thing happens to Murky.

Conversely, Young Vlad shows no signs of being able to rule with a heavy hand like his father, but he clearly still holds a great deal of social status in the Town because of his lineage.

Kin

They’re the reflection that humanity is part of nature, and not distinct from it.

Oyun portrays them as an ancient culture whose toxic connection to Mother Boddho has turned them into cattle. At first, it might seem disrespectful the way Big Vlad talks about them, treating them like animals. However, when even the Kin themselves talk about them using that term, I felt a differently about him. Big Vlad actually knew how to deal with them and give them a place that would fit them into the society of the Town. The Kin even mention that they would obey anyone who proved to be strong enough to lead them and to know the Lines.

They’re most likely inspired by the Buryats2, real-life indigenous people who live in the Mongolian steppes. Details suggesting this include, for example, the fictional steppe language which borrows terms from Mongolian. For example, Zürkh (зүрх) means “heart”, which is very similar to the name of Mother Boddho’s heart: Zurkhen.

In addition to the part of the Nocturnal ending where some of the Townsfolk become part of the new Town, it’s also revealed that you don’t necessarily have to be a direct descendant of the Kin to be a part of them. It’s more important for them to understand their culture and get rid of the I in order to become one with Mother Boddho. For example, Rubin could have become part of the Kin if it wasn’t because he hadn’t cut a human body without being a menkhu.

Conversely, any of the Kin can become Townsfolk. As secondary as Var may seem, he’s important to reveal this aspect by disowning the Kin and referring to them as “them”. Although it’s not explicitly stated, the same thing happens to some bandits of the Town at night. They even use knives to cut people, which is strictly forbidden if you’re not a menkhu.

The mixture between Kinsfolk and Townsfolk make the steppe language be not up to date, as there are new concepts in the Town that don’t have a direct translation to their language, which presents the disruption between the past and the future and proves Isidor Burakh right about that both worlds can’t coexist.

Executors

There are nameless executors (they appear as “Executor”) and three named Executors, but they all break the fourth wall. They are not to be confused with Orderlies, who are medical assistants who wear this costume at the order of the Bachelor to prevent further infection. Orderlies don’t have the meta-knowledge that Executors have.

Note that Executors have bones on both sides of their hood, while Orderlies don’t.

One detail that I didn’t notice at first was that the head of the humans wearing the Orderlies and Executors costumes are visible under the beak, as you can see in the pictures above.

Of the many characters who use the Executor costume, only three have names: Talon, Beak (whose roles are described in the Pantomimes section), and the Sand Plague.

The Sand Plague is a mysterious character who is initially referref to as ???. Once Murky’s introduces Artemy her friend, her name changes to Murky’s Friend, but it’s blatantly obvious that she’s the Sand Plague, because if we make the deal with the Changeling, who incarnates the Sand Plague at that moment on day 6, Murky’s Friend addresses us directly, without any middlemen.

Even though Murky refers to the Sand Plague in feminine terms, the face behind the mask of Murky’s Friend is the face of the Fellow Traveler, who, as we can see in the prologue, turns into an Executor.

Fellow Traveler

Though it’s not entirely clear what the background of this character is, we can safely say that he’s the personification of the Sand Plague and death. The first time we meet him in the prologue, he comes out of a coffin (how convenient) and tells Artemy that it’s a bit too early for him to show his face. It’s not until day 3 that the Sand Plague bursts, when death starts to do his job extensively.

As an outsider to the Town, the Fellow Traveler can be seen as an external entity to it, and not even a physical character at all, since the Whistler tells Artemy that he was the only passenger on the train that brought us to the Town.

He tries to gain our trust by running the Dead Item Shop, helping us by trading dead items for useful ones, and offering us a deal to avoid penalties for dying. It’s a character that obviously goes against Mark Immortell’s play, which he even addresses in the Deal ending.

He’ll try to hook us on his shop for the first two days, since the situation in the Town is not yet critical. On the following days with the Sand Plague, however, he’ll place the shop in infected districts, except on day 6, when he’ll place it far away from the Town to make us wonder whether it’s worth going there or not, wasting precious time on our way. He also gives us the opportunity to buy Inquisitorial Coupons on day 6, which are initially called “Candy Wrappers”. They don’t seem to be useful at this point in the story.

He tells us this before allowing us to buy them:

This is what he tells us before selling the Candy Wrappers:

Perhaps this is my attempt to save you, fellow traveler, giving away diamonds for the price of sugar. Or maybe I’m trying to swindle you, as befits a merchant (…) The stakes are your fate, fellow traveler. You’re sewn to yours with a double seam. Meaning, you can do anything — fate won’t let you go astray. Even if you don’t yet understand the meaning of your actions.

On day 7, the Candy Wrappers turn out to be useful, which will increase our trust in the Fellow Traveler. It’s almost inevitable not to fall into his trap at this point in the story, when he seems to be the only person helping us in the midst of pure chaos.

I’m curious to see the Fellow Traveler’s relationship to the Bachelor and the Changeling, if he’s relevant to them at all.

Rat Prophet

Magic clearly exists in Pathologic world, but it exists indiscriminately, which is reminiscent of the literary genre of magical realism. Along with the existence of entities such as Mother Boddho, Albinos, and Worms, the Rat Prophet also reflects this mystical aura.

Liberated from the theater by Mark Immortell as a punishment for dying several times, the Rat Prophet reflects the anthropomorphism of a human being in a rat, an animal that has been historically associated with treachery, filth, death, and plague. He’s another character that breaks the fourth wall, and while he doesn’t lie, he never tells the whole truth. The way he speaks is untrustworthy and suspicious.

The fact that a prophet in the Pathologic universe is a shady rat goes against the religious figure of a prophet, such as Jesus Christ or Mohammed. They’re associated with cleanliness and honesty, which is exactly the opposite of what this character portrays.

The Powers That Be

To me, this is without a doubt the most mysterious entity in the game. The game doesn’t give much information about them, as they are only mentioned a few times by the Rat Prophet and Aglaya Lilich, who describe them as a higher power that rules everything. It’s not clearly stated who they are, but it’s not crazy to say that they could be the representation of the studio, Ice-Pick Lodge, as they are the masters of the Pathologic 2 universe and the ones who make its rules.

These are obviously weak guesses with the little information given, but it will definitely be interesting to see how they are portrayed in Pathologic Classic.

Tragedians / Reflections

At first, they appear to give tips and supplies to the player. However, as the days go by, this role is swapped out in favor of appearing more as the inner thoughts of certain characters.

Their inclusion in the game is a brilliant way to give more insight into the psyche of the characters, as Reflections usually mirror their fears and struggles, something that isn’t often explicitly said by the character or us as humans.

The way they talk is quite formal and literary, which reminded me of Iwazaru from killer7.

It’s important to note the part of the last conversation with Mark Immortell, whether in the Nocturnal or Diurnal ending, where we can choose to take Mark Immortell’s place in the theater as the director. If we choose to do so, the Haruspex takes a step forward on the stage and bows, assuming the aspect of a Tragedian. It’s as if he denies his identity and becomes a nameless, generic Tragedian. Or perhaps he reveals his true self: a Tragedian playing the role of Artemy Burakh.

Conclusion

Pathologic 2 has proven that it’s possible for the video game medium to capitalize on player interaction to create a compelling story and world that allows us to be an active part of the plot development without abusing our choices in the explicit narrative. These aspects, combined with masterful ludonarrative design, interesting survival mechanics, richly developed characters, and a profound story, result in one of my most cherished artistic experiences of all time.

I’d like to end this review with this poem by Sam Garland3, which I think fits very well with Pathologic 2.

I had planned my first endeavour -

But the world had plans for me.I am lost,

but not forever.I am where I’m meant to be.

May Mother Boddho caress your step, emshem.

P.S.: I’m still shocked that I managed to finish the game on the intended difficulty on my first playthrough.

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

Credits to Whanmy for this description (not to be confused with whammy). ↩

-

Source. He’s also known as /u/Poem_for_your_sprog on Reddit. ↩