American Psycho (Mary Harron, 2000) Review

Materialistic emptiness.

Psychopath: a person who has no feeling for other people, does not think about the future, and does not feel bad about anything they have done in the past.

As civilization has established its hierarchies, the resonance of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave has grown stronger than ever. We have become a society of prisoners who prefer the comfort of projected shadows to the often painful glare of lucidity under the yoke of new social scales. In a society that privileges appearance over essence, individuals run the risk of becoming mere amalgams of labels, brands, and rehearsed gestures in search of external approval. When success is measured by how much money and power one possesses, regardless of how it was obtained, a person’s authentic identity and interests are overshadowed by a greed for material items that leaves an emptiness they cannot fill. It is in this rift, where striving for the social ideal turns into alienation, that one of the most lucid and uncomfortable works of our time emerges.

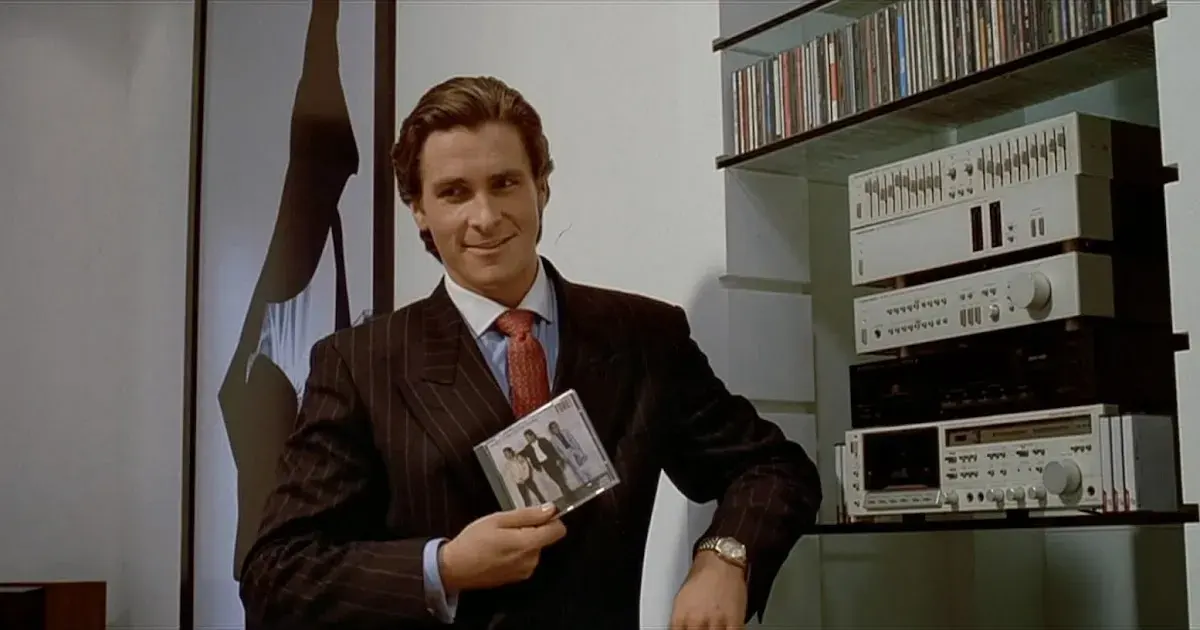

American Psycho is, at its core, a social satire that exposes the toxic masculinity lurking beneath a façade of perfection. Mary Harron fuses psychological horror with tinges of black comedy, evoking Happiness (Todd Solondz, 1998), while Christian Bale brings to life a cultural icon representing the reduction of the individual to elitist materialism, sexual depravity, and unbridled violence.

I have to return some videotapes.

Few phrases capture the essence of the protagonist, Patrick Bateman, as well as this one. Behind that trivial excuse lies an entire manifesto of contemporary alienation: a man who needs to disappear from his own world because he cannot bear who he is—or worse, who he is not.

Bateman is a grotesque caricature of the corporate male archetype. He is a human catalog of masks, all of which share a common denominator: he is polished, handsome, narcissistic, and obsessed with his body, clothes, and social status. From his morning self-care ritual to his Armani suits, everything in his life is a material ritual that conceals his profound inner emptiness.

Christian Bale delivers a brilliant performance, combining histrionics and restraint with a mechanical smile, an emotionless gaze, and forced courtesy compromised by the slightest brush against his colossal ego. Every gesture constructs a character who does not exist, but rather acts as if he does.

Bateman is blinded by a pathological obsession to stand out in a corporate environment dominated by formality and men with ties and expensive jackets. His role as the son of the owner of the company where he works—whom we know nothing about—is a living example of how social determinism has hijacked his free will, turning him into an archetype of the socioeconomic context he has been fed since birth.

Bateman’s narcissism is so fragile that any shadow of rivalry, even if involuntary, unleashes a homicidal violence intended to protect his pride. This same brutality extends to the sexual sphere, where his pornography addiction is just the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the surface lie his encounters with prostitutes, where he indulges in his most perverse fetishes. Despite a fleeting glimpse of sanity during a conversation with his secretary, in which he recognizes his irremediable condition, his murderous compulsion intensifies progressively throughout the film. I am certain that Bateman would likely identify with the protagonist of The House that Jack Built (Lars von Trier, 2017), who offers an explanation for this very sensation in this scene.

In Bateman’s sterile world, his attitude towards women is a natural consequence of his materialism. To him, they are not human beings, but rather interchangeable accessories designed to complete his “disguise” as a successful man. He treats his fiancée, Evelyn, with arrogant boredom and utter contempt; he keeps her by his side solely because society expects it of someone in his position. The situation becomes even more cynical with Courtney (Samantha Mathis), Luis Carruthers’ (Matt Ross) fiancée. Bateman uses her as a stolen trophy to assert his dominance over his colleague. For Bateman, seducing a colleague’s wife is not an act of passion, but a power play, a victory in the silent status war he wages against all the men around him.

Interacting with Luis Carruthers adds a unique twist to Bateman’s life by introducing the fear of being truly “seen.” While his colleagues and fiancée ignore his true nature, Luis projects a romantic fantasy onto Bateman that implies an emotional connection, albeit misguided. Bateman’s reaction to Luis’s advances exemplifies the terror a narcissist experiences when confronted with someone attempting to penetrate their emotional barrier. Ironically, Luis is the only person who tries to love Patrick for who he thinks he is. This unsolicited intimacy is the only threat to which the “monster” knows how to react other than by fleeing—or returning his videotapes, as he would say.

Despite the violence Bateman exerts on his victims, Harron and screenwriter Guinevere Turner understand that the key to the story lies not in the gore, but in his psychological profile. Throughout the story, we see events from Bateman’s perspective, which wavers in the face of hyperbolic violence and the schizophrenic episode he experiences. These facts force us to question the ontological truth of the murders, leaving us with lingering doubt, much like the spinning top in Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010). The climax of this uncertainty occurs when Bateman confesses his crimes to his lawyer, who addresses him as “Davis.” His confession is dismissed as a joke, even contradicting the facts gathered by Detective Donald Kimball (Willem Dafoe). Along with the confusion over his name, this opens the door to the interpretation that, in a world plagued by interchangeable men, objectivity dissolves into deep subjectivity.

The legendary business card scene is a metonym for this social dynamic. In it, identical men engage in a struggle over trifles such as the purest shade of white or the most refined typography, despite having the same generic corporate content structure. It is a war of hollow identity, where success criteria are measured by variables such as the thickness of matte paper.

Harron materially translates this vacuum with a clean, cold, almost clinical mise-en-scène. The minimalist interiors, pristine lighting, and symmetrical shots transform Bateman’s environment into a sanctuary of emptiness. Within those expensive pieces of furniture lies a veritable arsenal worthy of Unit 731 scientists, viscerally representing the physical-mental duality that defines the protagonist.

Bateman’s speeches about music, far from being a mere cultural nod, are transformed into a tool of irony. In his monologues about artists like Phil Collins or Whitney Houston, he prioritizes the delivery of his opinion over its substance, which he likely read in a magazine. Similarly, his fixation on restaurants is motivated by status rather than culinary enjoyment. Any aspect of his actions that we analyze invariably converges on his profound superficiality and his incessant drive for distinction.

Over the past two decades, American Psycho has acquired a prophetic character. Narcissism, brand idolatry, and the cult of image have multiplied in social media age, with Instagram and LinkedIn as its greatest exponents. It’s easy to imagine Bateman as a fitness influencer or a crypto trader today, exhibiting his existential void through meticulously edited photos.

American Psycho is about a sociopath who is a victim of his socioeconomic circumstances. Although Bateman’s perpetual pain due to his condition will never cease, as he states at the end, it is rare that we can empathize with him due to how dehumanizing the work is. Similar to the feeling left by works reflecting the concept of the “banality of evil,” when I see someone in a suit and tie with a façade of perfection, I can’t help but think of the dark side within.

Due to the vacuum of his identity, determining whether Bateman’s psychopathy is inherited or circumstantial is nearly impossible. Bateman is not an individual but rather a collection of symptoms and commercial brands. He exhibits psychopathic traits that seem intrinsic, such as his inability to feel real affection. However, his environment acts as a perfect breeding ground that validates and amplifies his darkest instincts. Bateman is not a person born with mental illness due to biology; rather, he is the archetype of a socioeconomic context that blurs the line between the individual and the power structure. This suggests that, in a dehumanized world like his, psychopathy is simply the most efficient adaptation mechanism.

The true horror of American Psycho does not stem from Bateman’s crimes, but in how easily the spectator can see their own neuroses reflected in his. We have all felt, to some degree, the anxiety of seeking social validation, the fear of being overlooked in a competitive social group, and the obsession with projecting an image of success. By making us laugh at his frustration over not getting a reservation at Dorsia or the inferiority of his business card, the film sets a trap for us. In some way, we also participate in this theater of vanities, and that, like Bateman, our identity is sometimes built on pillars that are just as fragile and superficial.